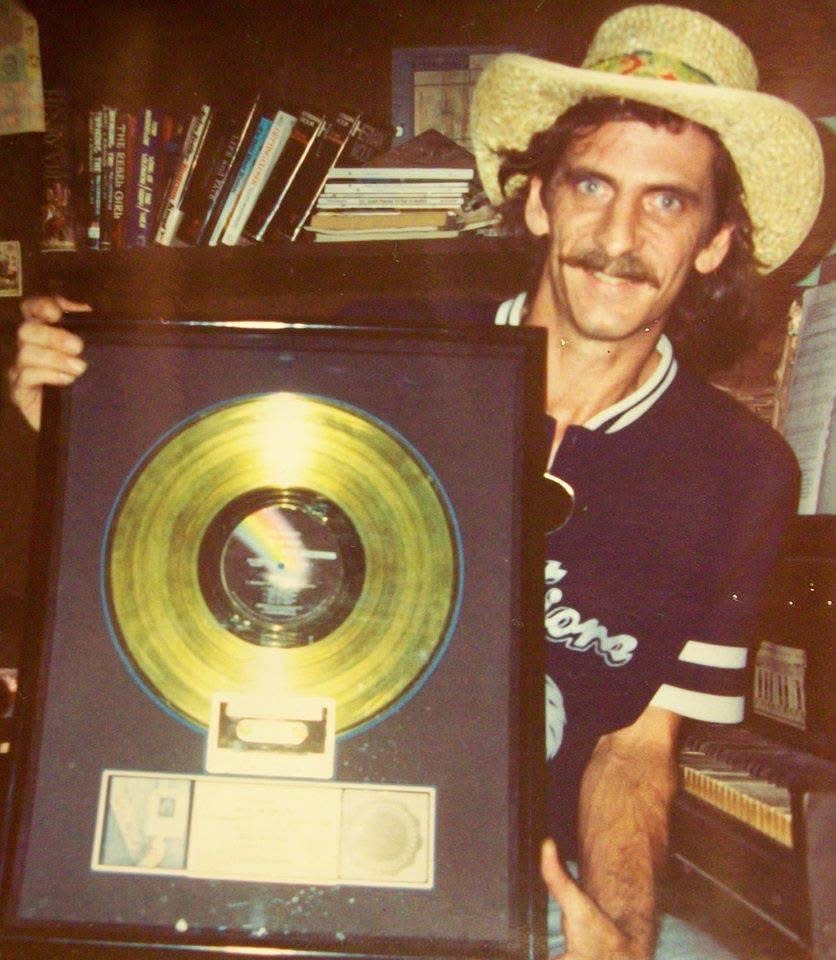

Featured photo of Michael McGeary by Nancy LeNoir.

Boom-ti-tok-ti

Boom-ti-tok-ti

Boom-ti-tok-ti

BOOM.

“Hi, Buckaroos.”

Jerry Jeff and that little airy half laugh; you can hear the grin on his face.

“Scamp Walker time again. Yeah, I’m tryin’ to slide one by you once more.”

And, as always, he successfully slides it by — and the next thing you know forty-five minutes have dispersed into the ether and you’re sitting there slack-jawed as he and The Lost Gonzo Band go home to that armadillo over and over (and over) again and ¡Viva Terlingua! fades ecstatically into the runout groove.

Alright; so that’s just how it works. But let’s go back and try something different. This time, as soon as you hear that BOOM: Hit pause. Then repeat.

Listen to that honky-tonk two-beat skip out front like the advance guard. Maybe it’s not wholly dissimilar to other country beats you’ve heard, but it’s like that hi-hat knows what’s coming and, like Jerry Jeff, can’t quite keep from smiling.

And did you catch the atmosphere refracting through each wooden tok? You can almost just make out somebody saying something somewhere back there in between. What is it? “Take six”? I don’t know.

But it feels like there’s some kind of magic trick or Bloody Mary invocation going on here. “I swear it works! Here’s what you do….” You sneak into the old Luckenbach dance hall on a hot, summer night and rap this drum three times, then… ta-da! ol’ Scamp Walker himself will somersault through the door doing jazz hands, and he’ll grant you your deep, unspoken, probably unconscious and heretofore unknown desire… for the perfect “Texas” album.

And what he’ll present you with is an embarrassment of riches. Like a giant washtub of his famous sangria wine, ¡Viva Terlingua! mixes in every ingredient Jerry Jeff Walker and the Lost Gonzos could get their hands on: bouncy golden-age country, moody ballads, honky-tonk, rock and roll, a pinch of soul and psychedelia, and even a ragged, decidedly non-Texan (or maybe completely Texan, for that matter) shot at reggae.

That unusual genre choice, as well as that iconic percussive intro, comes courtesy of a “weird-ass hippie guy from L.A.” decked out, not in cosmic cowboy attire like his Gonzo compadres, but in “embroidered genie shoes from Afghanistan or something.”

—

Michael McGeary: I also had these mattress-ticking shorts my girlfriend made for me. I needed some closed-leg shorts. I used to go commando – it’s the only way to hang — and had once been told the family jewels were visible from the audience with regular cutoffs.

[laughter]

OK. So, ¡Viva Terlingua! …You and your drums are the first thing we hear on the album.

MM: The opening beat was a complete surprise to me, but it’s sharp and on time so I’ll take it! Kinda cool – I was never the first heard before!

…But, first, what possesses you to write this?

Well, I want to know what really happened in the recording of this album; I’m not interested in the myths – unless they’re true, of course! After all, whatever the truth is, you guys managed to create the best album to ever come out of Texas. And I’m fascinated by the community/group effort of it. It was Walker’s album, but Gary P. Nunn got his spotlight, for instance, and I know that “Sangria Wine” wouldn’t be what it is without you. You guys made something that has deeply affected a lot of people, and I know more than a few who want to read something other than the same old recycled stories.

MM: Well, I’ve seen the narrative repeated ad nauseam for over fifty years; I’ve been asked about or read about this whole thing so damn many times I’m losing track of the mythology. Some of it comes from rehashing old articles by various and sundry “music writers” – some from folks who were there. The “Austin Interchangeable Band” label was just some writer’s description of what was sort of a loose tribe of guys jamming informally. There were certain musical styles, licks and formats we all knew so it was easy to sit in with guys from different bands. But we were [Michael] Murphey’s band and were never “interchangeable” but for a few times.

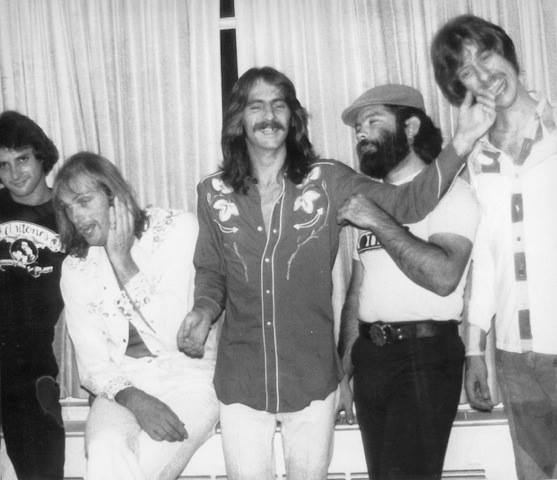

The “Austin Interchangeable Band” was actually The Lost Gonzo Band, originally named “A Deaf Cowboy Band” after a review that called them an “adept” cowboy band. For a brief period spanning 1972 to 1973, drummer Michael McGeary, multi-instrumentalist Gary P. Nunn, bassist Bob Livingston, guitarist Craig Hillis, and steel guitarist Herb Steiner backed both Michael Murphey (later to be known as Michael Martin Murphey) and Jerry Jeff Walker when they were both based out of Austin, Texas. In ‘72, Nunn and Livingston played on Murphey’s Geronimo’s Cadillac album, and then all five Gonzos came together on Walker’s self-titled MCA Records debut a little later in the year. In ‘73, they made Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir with Murphey, after which McGeary led a band rebellion – resulting in what he calls the “morph from Murph” – which in turn culminated in the reason we are gathered here today: Jerry Jeff’s ¡Viva Terlingua!

MM: Jerry Jeff blew into town [in ‘72] shot-loose with a record due and no band, so Murph lent us to him for the “brown album” [Jerry Jeff Walker] since he was in town and so was Murphey. That album was kind of a rehearsal for ¡Viva Terlingua! — but even funkier. There’s no engineer at all! All the mics go straight to an 8-track on wheels, volume controls on the deck, no EQ, two drum mics, etc.

Man, if you knew both Jerry Jeff and Murphey you could get a feel for what a mindfuck it was to play for both of them. Playing with Murphey you had to know how to play music; with Jerry Jeff you just had to know how to play with Jerry Jeff. Murphey was intellectual, rigid, and straightlaced. A good wordsmith but almost completely lacking in funk. Like Jerry Jeff, I was never able to warm up to him or he me.

You weren’t able to warm up to Jerry Jeff? Or to Michael Murphey?

MM: Neither one. But, you know, I can look back, at my age now, and see that there were a lot of factors that entered into that lack of relationship.

I was kind of a weird-ass hippie guy from L.A., and I carried a lot of Hollywood attitude when I moved here in 1970. I ‘d been hearing about Michael Murphey and Jerry Jeff Walker; they were practically deified in the little world of Texas Folk – Murph mainly for writing and Jerry Jeff mainly for longest rap sheet. I was from Hollywood where we had a saying: “Sincerity is key to success, and once you can fake that you got it made.” I was suspicious of these self-styled characters, but I had to get along – I knew no one in Austin, and I couldn’t go back to LaLa Land.

It was all wonderful and new and baffling and scary. I lived in flight or fight mode most of the time so I maybe didn’t come off very friendly. I was also not in the guitar club, and this entire culture is Martin Guitar driven. I never seen so many f’n guitars! Music was done a whole different way here, and I had a lot to learn. A lot of the interaction and lore and colorful bullshit all happened in that circle of pickers swapping songs, but I could only tap on something from outside it – very frustratin’! I was only needed when the full band was on a gig, otherwise I was a fifth wheel just hangin’ out – an alien in this world of guitars and hats. (There was never any place to sit in the dressing room because there was a freakin’ guitar case on every chair!)

Anyway, Murphey was haughty but skilled in a clean, efficient way. Jerry Jeff was always desperately hunting for the soul of down-home, late-night, beatnik cowboy funk or some damn thing. He was constantly seeking the deep, psychic soul of the original caveman folk singer.

[laughter]

MM: You gotta understand, I walked in from Hollywood right into an established musical ecosystem that reached all over the country, with customs, stars, legends, poets, characters of all stripes, a web of clubs, coffee houses, colleges, and bars connecting them all, and down-home fan support like I never knew existed. There was no going back.

McGeary grew up in San Diego, where he sang in the Catholic Church choir and went to high school with Kelly Dunn and Joanne Vent, who both appear on ¡Viva Terlingua!, playing organ and singing backup, respectively. Kelly and Mike were childhood friends and made music together – Kelly on guitar and Mike on drums. (“And what a coinkydink that [Joanne] was there, too!”)

MM: Kelly and I were inseparable pals since age twelve. We met in after-school catechism classes required because we went to heathen public school. We both liked music. He could play Chuck Berry, and we sounded just like the Everly Brothers in the right key. Until puberty came along and wiped my voice out. I had this really high, pretty voice, and we’d sound just like ‘em. It was cruel news the day the priest sat me down and said, “Michael, your voice is changing,” and he described the descending testicles. And I went, “Oh no!” He said, “Yep.” And that was the beginning of a year of a cracking, squeaking voice – so embarrassing! God, I never knew what was going to come out of my mouth.

[Kelly and I] were co-conspirators and misfits; neither of us were socially popular or in any cool clubs. He was the coolest person I ever met, and he was my reference for the coolitude of all things. We had a similar sense of humor and style. We were a little above average intelligence and were both in the honors classes at Hoover High. It didn’t take much to be considered a “discipline problem” back then, and we found ourselves in the principal’s office more than once.

His mom had died suddenly just before we met and his dad worked, so we hung out and snuck smokes which we stole from the nearsighted shopkeeper. We had a band called The Regents and were in a couple other union groups that played military gigs. There were hundreds of functions going on with the Navy, Marines and Coast Guard, so a dark suit/white shirt/dark tie/black shoes was part of my wardrobe.

In 1963, Mike went into the Air Force, from which he was honorably discharged.

MM: In the Air Force, I was in the NORAD Band, a prestigious musical outfit made of the best players from all the services of the U.S. and Canada. Very hard to get into, but that’s a whole ‘nother story. I was assigned to the NORAD Color Guard, a precision drum and bugle corps. I learned military drumming – a strange direction for me, but I was really good!

Kelly went into the National Guard and was assigned to the Watts riots. After getting out of the service, they played jazz, rock, and pop standards (“the hamburger and french fries of music”) at parties for returning ships, one of which carried Marines just back from Vietnam: “The guys had hollow stares, drinking cans of Schlitz, one 3.2 % per guy – they didn’t clap or react.”

A little later, Mike found himself in L.A. playing with the Standells of “Dirty Water” fame.

What was it like in the Standells?

MM: The Standells were not a close-knit group in any way, shape, or form, but I got along great with Tony Valentino, ‘cuz he was a great guy, and he was kind of funky. They had been a top touring act about three years before, and, in L.A. at the time, I was starting to get a taste of what it was like to meet these bands that had been on the Top Ten a year or two or three before and were still there. You know, like Sean Bonniwell and the Music Machine? And the Seeds? I just wanted to get on with some rock and roll band with long hair and gigs and play on the stage and have lots of girls and dope and live a glorious life. I just wanted to escape, man. I just wanted to get out, and my drums were my ticket to the circus.

So, they would call me up and say, “We’re gonna come and pick you up Thursday and we’re gonna play at this college or that college,” and we’d go there and play this gig, and they had one set list. It wasn’t very much of a boogie; it was very clinical and pretty much, “Let’s go knock off this gig,” right? But Larry Tamblyn wants to spice it up. We need to do something with this band; it needs to graduate into the psychedelic era somehow. And so Lowell George [later frontman of Little Feat] shows up. He was fucking good.

One day, Tony comes by and gets me, and we gotta go pick up Lowell for rehearsal. Lowell is living in one of those houses that had been divided into a bunch of apartments, and so it made for some very weird plumbing arrangements. In Lowell’s case, his bathtub was in the middle of the kitchen. When we get there to his apartment, we’re banging on the door and no answer; we can hear music, though. So we poke our heads in saying, “Lowell, what’s up?”, and Lowell is in the bathtub. He’s taking a bath; he is not ready. And he is in a fucking sour mood. Turns out that [his girlfriend] has dissed him, and he’s not well. I remember that incident every time I hear the [Little Feat] song with that line, “There’s a fat man in the bathtub with the blues.”

I’ll tell you what he did, though. He helped me a lot, because we did a Japanese candy commercial, and it was my first time in a real studio. [Standell] Larry Tamblyn was a well-known talent, so when we went into a studio, we went into a nice one. So we played for this commercial, and Lowell took me in the studio, and he played the drums back. And he says, “Look, your foot and your hi-hat and your snare drum are not hitting at the same time. Look at the meter.” And he showed me. And he said, “You’ve got a good command of your foot, so when your right hand hits that hi-hat your foot hits the….” In other words, he pointed out, “You don’t have as good a control of that as you thought.”

Did that bother you?

MM: No. I mean, he said, “I got you on tape.” You cannot argue with that. And every guy wants that, even if the news is horrible, which often it is. Every guy wants that time when you get in there and you record, and then you go back in and hear the evidence of what you really sound like, as opposed to what you think you sound like. And how you play and what you sound like in a studio, it’s an ocean-size difference from the stage.

The L.A. scene was exciting. Mike worked at a place called Family Productions and was drumming in the studio one day when Ringo Starr walked in. (“I jammed with Ringo.”) He saw George Harrison at The Rainbow Grill. (“I told him, ‘I love your band.’”) Once, while making deliveries for Polly Bergen’s cosmetics business, he rang the bell at someone’s house only to have Paul Newman open the door with a pool cue in his hand.

MM: [Kelly and I] dreamed of being stars and having that gold record and eventually we did get them – and in the same band for the same thing. Very unlikely that it would be Texas folk, but that’s how the cookie unfolded.

How did Kelly end up playing on ¡Viva Terlingua! with you?

MM: He was bored in San Diego so he came out to see me in Texas; I was rehearsing with Jerry Jeff then, and he just sorta latched on to the clusterpick (Craig Hillis’s word!) and was absorbed. Jerry would take a liking to some weirdo and they would just magically be in the band.

Being from California, how did you wind up a part of the Austin scene in the first place?

MM: Ray Wylie Hubbard – before the “Wylie” – brought me to Texas from L.A. where I was an actor in the first improv theater company when it was just a concept and that crazy man Del Close was the director. We were essentially a workshop extension of The Committee.

Were you trying to be an actor?

MM: I did not know what was going on, but what I wanted to be was in the group. I wanted to be included; these were the fucking coolest people I’d ever met. They were turning me on to ideas and concepts…. I mean, I knew nothing. I was quite amazed that they let me into the group. One of the guys in the company was Roy Applegate; he was from Dallas, and he knew Ray Hubbard.

We had a party at one of our members’ houses, and at this party was Roy Applegate’s friends’ group from Dallas called Three Faces West [featuring Ray Wylie Hubbard, Rick Fowler, and Wayne Kidd]. They were in town because they had been booked at The Pasadena Ice House to open a show for the Dillards. I was never really sure how they got booked at the Ice House, but that’s a very prestigious gig in the folk world. I brought my drums over to the house where they were staying, and we played a few tunes and it sounded so fucking good, man. They asked me to play the show with them. I’d been in the band for like three days, and they asked me to play the most important show they ever did.

I was devoted to that band. It was one of the times when I had no desire to promote myself or my playing above that of the group at any time. My job was to blend, to push it a little bit, to put the edge on it, to make that band rock gently hard. And they liked it, man! They had never worked with a drummer before, and so it was really fun, and they cared for me, and they treated me like a brother from the beginning. They had me out here in Texas, and talk about a stranger in a strange land. If I’m not able to get along, where do I go? I go get a dishwashing job somewhere – in Texas where nobody knows me.

Later, I was in [the band] Texas Fever – which was Three Faces West after Wayne left – with Ray and [Bob] Livingston, just off the road one night, ready to sleep for a week, when the phone rings and it’s Gary P. Nunn [who was playing with Michael Murphey at the time]. He says they can’t find [their drummer] Donny Dolan, and they’re opening for Elton John that night at the Coliseum. I had never seen Murphey before, but Texas Fever played some of his songs, so I showed up to a packed auditorium, met Murphey, set up, quick sound check, and then we were off. Him, me, Hillis, and Nunn.

Gary was my pilot through that show, right there at the kit, counting bars, giving cues, turning so I could see his hands and see exactly when he plucked (very helpful!). It was flawless and I was given the gig. Livingston left Texas Fever when Ray went electric, and Murph brought him on. So that’s how I got hooked up with Livvy and Hillis and Nunn.

One of the biggest mistakes of my career was to go with Murphey without saying goodbye or giving notice to Texas Fever. Like I said, I was devoted to them. It was the first really popular “A-list” band for me; I was recognized and respected in that world, and it was just the best thing ever.

Getting into Murph’s band was a major coup; he was top dog in the territory, and it put me among the elite players of that world. It went straight to my head.

I need to go back to Gary, though, ‘cuz without him none of this ever happens. In my opinion, Gary Nunn is central in the larger saga of the cosmic cowboy “thang.” He was the pilot: arranging, singing, imagineering, and my reluctant guru of drumming. He was a nitpicker, but truth is, at the time I was relatively inexperienced in how to play with these Texas songwriters, so he got me thinking simple and supportive. It was hard ‘cuz I was too complicated and “L.A.” in my style.

Nunn was band honcho for Murph. A multi-instrumentalist, he was a singer/songwriter himself. He put together arrangements and thematic riffs for Murphey’s particular style, and he interpreted Murph’s ideas. He’s the power behind the throne on these records – especially ¡Viva Terlingua! And in shifting from the Murph mindset to the Walker mindblow, Gary is the oil in that machine.

You know, on Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir there is a true musical marvel: [Murphey and Nunn’s] “South Canadian River Song” was done all at once, with everyone live in the room in one take. The take you hear on the record is the only one in existence. Gary’s piano part is transcendent, and the band fits in around it like a ghost glove. The kicker is that for reasons I never found out, he had to play it in E flat. If you are a musician you know – if not, ask one – about E flat… a difficult key.

That’s nuts, because it’s beautiful.

MM: Front to back. Live in the studio. That’s all of us looking at each other and playing soft like that, and then building back up. And Nunn, if you listen to some of the licks he plays, and then go, “Fuck, the guy’s playing it in a strange key!” – I don’t know if you’ve ever played anything in E flat, but on a piano it’s finger spaghetti, man. Very impressive, and he plays some licks on there that are still some of the coolest fucking licks I’ve ever heard.

I’ve heard that you might have been the instigator for the final Gonzo exodus from Murphey to Walker.

MM: [For Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir,] we went into Ray Stevens’ studio in Nashville with Bob Johnston, [Bob] Dylan’s producer, producing. Dates and time escape me, but after the recording was done we got paychecks from Johnston’s organization. With great dismay I saw what he had done.

This takes some explaining: Nashville is a solid union town; we had to be carded up to play there. The union enforced pay scales vigorously. There is an hourly wage rate, and what is called a jingle rate. Jingle rate applies to commercials, music bites, some film scores, but mostly ads. The union figured a player could do three thirty-second ads in an hour. The scale rate was much higher in cases which earned royalty (or were intended to). Murphey was the latter, a commercial artist. Johnston owed us scale, but the checks were for jingle, about two-thirds less. After all we did, on a meager retainer, rehearsing for this, getting it in five days, it was a slap in the face.

It was like this: We got our checks, and I looked at the contract, and I looked at the checks. And we were all going, “Fuck, man.” Because you gotta understand, this album was supposed to be the culmination and reward for months of arduous dedication we did for Murphey to get this album right and to do it without him. Because he couldn’t talk or speak; he had polyps on his vocal cords that required surgery, and he was ordered not to speak. We met everyday and went over the set, with Gary and Bob being Murph. It was an extraordinary effort. We were pissed.

So I bitched, and I didn’t go to Murphey, and I didn’t go to Johnston; I went to the union. I was raised union; my old man founded a union: American Federation of Teachers. I took a workingman’s view.

Now, it was an incredibly impulsive move; it was a move that only an amateur like me would make in Nashville. Because everybody there understood. First of all, getting to play on a record produced by Bob Johnston… shut your fucking mouth and take the check. Second of all, you better be pretty badass before you go wandering around waving your paycheck, because Kenny Buttrey [and other session players like him] are waiting right next door.

But anyway, I went to the union, and I bitched to the guy, and this associate agent was telling me, “Well, we’ve been trying to get him for doing this for years. He does this all the time, and nobody says anything; he’s got everybody intimidated. So… if you never want to play in Nashville again, we’ll file this complaint.” And I said, “Go ahead.” I signed a couple things and showed him my union card. He said, “I’ll be in touch in a little while,” and he took down my number. So I thought, “Alright, man; I’ve done it.” You know, and I went back, and I told the guys, “Alright, man. They’re not gonna get away with this shit.”

A little while later, Murphey calls us in the studio and buh-lows up. Apparently Bob Johnston has called him and goes, “What the fuck is up with your fucking band, you dick?” Etc., etc., right?

I should have mentioned my umbrage to Murph, who would have maybe inveighed upon Johnston to produce the gelt. It was a big stroke for the record company to get Bob Johnston to produce the record in the first place, and so now they have Johnston furious at Murphey; the record company is upset with Murphey… and so it’s not a good thing, and he yells at us, and he fires us all. “You’ll never work on any album of mine ever again! You’ll never play with me ever again!” Kicked us all out, so we took the van. We got the keys to the van, left all of Murphey’s stuff in the motel, and took the van and hauled ass.

We got our money a week later.

That rebellion was a key turn of events. Had that not happened, we would most likely have continued with Murph. Jerry Jeff would have had a different band.

Wow, yeah. Gary P. somehow stayed in Murphey’s good graces, right? Obviously, he still had “South Canadian River Song” on the album.

MM: Yeah, I mean, he’s got a song on this album, and he gets to go to England. His adventures in England were less than he wanted, but….

Yeah, but they gave him “London Homesick Blues”….

MM: I don’t blame him for going.

Did you ever make up with Murphey?

MM: Me? I never spoke to him again.

Really? Did you avoid him, or did y’all just never cross paths again?

MM: No, [we] have no interaction because he doesn’t live in my town. Every now and then he’ll go out on some tour, and he’ll call Livingston and Herb, and sometimes Gary, and they’ll go play with him.

Were you on bad terms with the band?

MM: The thing about it is I started to get in a little trouble with the band because I had gone straight from high school into the military, and almost straight out of the military into a band where I got into shit with the band leader, you know? I had a history of it. I just didn’t know how to act. My drumming was good, but I quit paying attention to keeping the band stable and making the song sound good. And I started kinda winking at girls in the audience that looked cute. I just couldn’t fucking buckle down and play.

I get on bad terms with Jerry Jeff, and I get fired, and Jerry Jeff doesn’t even tell me. I had to go find out that there was no ticket for me at the airport, and that Donny Dolan was going [instead]. I told [Jerry Jeff], “Man, alright, you’re gonna fire me, but you need to get me a ticket home.” So he gave me the money to go home, and that was the last time I ever spoke to him.

That’s too bad.

MM: No, wait! No… I did his Paramount concert and then [a show] out there in Luckenbach. We went out there and played one time on his birthday.

Did you ever play on any more of his albums?

MM: No.

That’s unfortunate. Your drumming is so important on ¡Viva Terlingua!, for one thing.

MM: I don’t generally point that out; I’m pleased when somebody else does, and it’s been a couple three people that have.

You’re crucial on it.

MM: Well, so is everybody. I mean fuck, man.

I know; that’s part of the beauty of it.

MM: I finally put that record on recently with a good set of headphones. I had no idea it was so deep and rich. And you gotta understand, man… pre-digital age. This is just in a barn [actually the Luckenbach dance hall]. With a truck.

[Engineer] Dale Ashby and crew did a great job on that.

MM: It’s beautiful.

Folks have been trying for years to glean some secret from this record, some mystical indicator… the X marks the spot of the soul mine. It has been glorified to the point of disappoint, so to speak. But partly it’s the sound: warm acoustic with no juju on it. And the order of songs is great, with “Redneck” and “London” live to spice the feeling.

I’ve heard Jerry Jeff tell the story of how he got the call at home that Ashby was already in Luckenbach set up and ready with the truck, and he thought, “Uh oh, I better write some songs….”

MM: Jerry Jeff was not ready; he didn’t have the songs, or he had half a song…. He was always going off by himself to finish or write a middle for something. He was intractable; you had to corral him into recording.

So let’s talk about “Sangria Wine.”

MM: The “Sangria Wine” yarn. The myth is that this was a major part of doings and that everybody was whacked out all week on wine and weed. Nuh-uh! Beer was a constant, as you might know, and there was some weed around but only at or below normal level for this bunch. We were all old hands and had tolerance and also could play high, but I’ll say that in my experience music is a higher place anyway, so there’s wiggle room. Jerry could get out there out of control – and often did, as part of the character – but I don’t remember him being really fucked up during this. There was no using while recording; the band culture was not real dopey or boozy.

I recall just one trashcan batch [of Jerry Jeff’s homemade sangria wine] whipped up on a hot afternoon – gallons of cheap red wine and whatever fruit there was in [nearby] Fredericksburg, Texas, that day. Jerry Jeff was enthusiastic; the rest of us quietly dubious. It was horrific. To pay a compliment, everybody had a little; I smiled and sipped and surely killed the bush I poured it out on. How many C’s in YECCCH?

The song, however, came as a slightly drunken jam. I don’t recall it ever being written out. I had picked up on reggae during a trip to Toronto where there is a whole Jamaican section of town; I was an instant aficionado. I thought this budding tune could be done reggae…. How to lay this on them without causing frustration was the task. It was a two-part riddim in my mind, but I decided not to complicate matters and just give them one to settle into. Jerry would just blow it off if he felt any difficulty, so I didn’t even bother to try to get him to play the guitar part. I also let go of the reverse rhythm of reggae so as not to confuse anybody (it woulda drove Gary nuts; the backbeat in reggae – it’s like three guys pushing a car and someone jumps in and pops the clutch). It’s sorta cowboyreggalypso. I think it helps. Otherwise, it would have been just another Jimmy Buffett song.

Can you tell me your story about the spider?

MM: Well, in the barn where we played, what we used to separate the drums so they didn’t bleed all over each other’s microphones were hay bales. So I had a stack of hay bales around me, and I’m playing along and we’re playing that song called “Get It Out”; we’re thumping along on that. And I feel something, and I’m looking down, and… you know, there’s a variety of spider down here that’s about as big as your hand, and it’s black and yellow and all those alarming colors. It screams danger.

So, this spider is climbing up my body, and he’s going along good and he’s got these little hooks on him and he’s climbing up and I’m going, “Oh, fuck.” I feel him on my arm, and I go, “Oh, man,” but I ain’t stopping – the take is rolling. I couldn’t find a way to get a break to brush him off, so I just had to deal with it. Before very long he had climbed up onto my shoulder and across my neck – aaagh. I had my hair gathered up, and he stumped across me, and I’m sitting there – I’m about to fucking scream, but I’m keeping it up – “Get it out….” But I’m going, “Get it off me!”

The spider just keeps crawling along, and apparently it’s not real fun; the terrain is moving around on him a lot. So he gets down my arm on the other side and drops off onto the head of the floor tom-tom. Now, you realize of course during all this music playing, the head of that drum is vibrating furiously. Even if you’re not hitting it, it’s all that music all around. So this spider is bouncing around like you dropped it in a hot pan. It’s just leaping around like, you know, sizzling. And I just caught a little second there and worked in a little thump on that floor tom-tom. And I hit that head real hard, and that spider just launched. He went flying out the window with a tale for his mama.

[laughter]

Have you read Livingston’s story about recording “Wheel”? How you all showed up tripping on the Sunday after the show, and Jerry said “we’ve got one more song to do,” and you all somehow held it together to record it. Do you recall that?

MM: Ohhhhh yeah! I watched his head float across the room – I was so high I forgot to play. I was so tripped out. It was [producer Michael] Brovsky who found us in our hideaway and dragged us back out to play. It sounds more together than I remember; there was no second take that I can recall.

There’s another indication on the album of how tight at least me and Livingston got to be, and that is “Backslider’s Wine.” Now that song is slow. That is dead slow, man. And if you listen, the kick drum and the hi-hat hit together every time. That is fucking hard to do, my man. It’s real easy to get ahead of or behind that beat, and so dead slow like that is really a test of your chops as much as a fast one is, for sure.

So, did you enjoy your time in Luckenbach? Was that week fun?

MM: I think I liked it! [laughter] It was a lot of laying around. There was a lot of boring stuff, and I had to keep my distance from Hondo Crouch and his chewing tobacco; I didn’t want him spitting on my shoes!

So you didn’t hang out with him a whole lot.

MM: Nah. [He and Jerry Jeff] always wanted to stay up all night and tell crazy-ass stories, and they would get all drunk and get maudlin: “It ain’t like it used to be. This world is going to shit.” [Jerry Jeff] wants to sit up all night long ‘cuz he can’t go to bed; he can’t let go of the search, you know.

Anyway, I just hung around all day and night and just waited for something to happen until finally they would coalesce around late, late afternoon and start fooling around with songs.

What memories do you have of the actual live show? Was that as great as it sounds on record?

MM: Oh, yeah. It was a great show; I remember that show. It was just a lot like the Jerry Jeff shows we played – all his shows were like that. People went berserk for this guy.

So, what made you stay in Austin all these years once you were through with Jerry Jeff?

MM: Well, part of it was money, and another part of it was that in Austin I had musical opportunities I’d never had, and I had some panache behind me after having played with all those guys. And I just landed in that tribe. It was all interconnected; I had a network of people that knew each other. I had a way to be seen and to get my talent spread around and get the word out.

I know that you played with B. W. Stevenson; are you on any of his records?

MM: No, he was making a record at the time, but the studio insisted on their own studio guys. So he left us home on salary while he was out there. Buck was quiet, unassuming, and very down to earth. A square-dealing guy with respect. Now, if you want to hear what we all did in his band, go to your little computer and look up the Five Minute Weirdo Band. That was one of the happiest bands I was ever in. We gigged while he was out in L.A, and there are several tunes from a live gig at the ‘Dillo [online]. Really good band.

But then I had this terrible decision to make: Should I stay with B. W. or should I go with this new band that gave me a chance to be a stage guy – to just show all these ideas I had. I was really into it. And so I bid B. W. farewell and went with Balcones Fault.

You sing a couple of the songs on the Balcones Fault album.

MM: Yeah, yeah, I was a front man of the band. The live show was a lot of me, and a lot of my arrangements, and a lot of my stage direction. You can go online and find some Balcones Fault videos.

How did you end up with The Lotions?

MM: Well, my tenure with Balcones Fault came to a crashing end. We moved to San Francisco and stepped into a league where our first show was with the Tubes. And those bands out there – they were San Francisco-, West Coast-show bands. And we just stood there with our fucking jaws in the dirt. So I ended up in San Diego working for my dad.

Doing what?

MM: Electrical construction for the Navy, until I saved up enough money and got a drive-away car – this lady needed her car delivered to Brownsville. So, I drove her car to Texas in November, and it was cold, and I had no heater in that car. My feet froze, and I was in terrible shape by the time I got to Austin. My girlfriend Cindy took me in at four o’clock in the morning. I was frozen stiff, and I had developed a cold, but I was determined to get to the Armadillo to see Toots and the Maytals. I had gotten their record on tour with Jerry Jeff, and I was way into reggae. I was gonna make that show.

And I made it, man! Sniffin’ and feeling like shit, you know – wrapped up in a heavy coat. That’s how I met Dave Roach; he was standing next to me in the crowd. So we started talking, and it turns out that he and his friends were into making up a group, and they were looking for a drummer.

At our first rehearsal [as The Lotions], I remember we got all set up, and they start in with “No Woman No Cry.” They start singing, and I’m going, “Ohhh yeah. This’ll work.” And then, when we got into the rhythm part of the song, and it became obvious that I knew what to play, it was like everybody goes, “Ohhh yeah. That’ll work.” So it was just this realization: “Oh fuck, we’ve got a guy that knows how to play reggae.” And so I stayed with them, and we were the only reggae band [in Austin], and man we used to fucking work.

I was in the thick of the scene down here; I played with a lot of bands, man, and I was in a lot of other little groups on the side. I arrived in town in the early 70s and within a couple of years I’m one of the big shots. There was a time when there weren’t many players here, and so I was everybody’s drummer. Of course, the town filled up as years went by, and that situation got diluted, but it was quite an amazing thing to touch all these different groups. It was a really incredible time.

What are you up to these days?

I have always secretly wanted to hide in my little workshop and build things. I had woodworking in school but could never do it while a musician. When I got to about 50 it was clear I was only going to get older and get less work — and the drums would be getting heavier every year. I started a biz in my garage making bookcases and eventually went into repair and restoration of antiques. Woodworking, unlike music, has solid standards and methods, and you can’t get by on BS. The emotional stress of dealing with others is relieved. I’ve built a solid, dependable service with a good reputation, and I am king in that shop. It’s good to be king.

-30-

Leave a comment