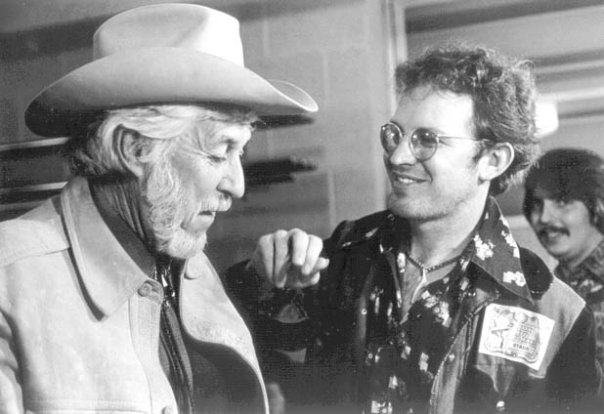

Featured photo of Gary P. Nunn by Gary P. Nunn.

Gary P. Nunn was born in Oklahoma, in 1945, but that’s beside the point. “Gary P. Nunn,” the Texas music legend, was born fully formed and pretty much wholly unexpected on August 18, 1973, on a little wooden stage in Luckenbach, Texas, in front of a crowd of hootin’ and hollerin’ cosmic cowboys and cowgirls who’d driven or hitchhiked the hour-and-a-half from Austin and paid a dollar each at the door to see Jerry Jeff Walker and band on that hot Saturday night.

I mean, yeah, Nunn had started out on drums something like fourteen years earlier and had then played bass and guitar in several hot regional groups from west Texas to Austin before working on a couple of major-label records with Michael (Martin) Murphey and one with Walker — but in a stunning, seemingly out-of-nowhere, seven-minute-and-forty-five-second extended flash of brilliance caught live on tape he was HERE — here in the collective consciousness of Texas music fans permanently and irrevocably.

—

Twenty years later, when I was 16 or 17 with the Beastie Boys or Pearl Jam or some other “alternative” thing sitting idle in my CD player, my mom sent me down to our basement to pull out some old record called ¡Viva Terlingua! by Jerry Jeff Walker. I had a vague idea of who Walker was, as I knew he was somehow related to other Texas country guys like Michael Murphey and Steven Fromholz, whose songs I’d grown up hearing ‘cuz my dad would sit at the kitchen table on a weekend morning playing his guitar and singing every last one of ‘em.

Mom told me to take the album to my room and check out the last song, which I did. My eyes widened. I listened to it over and over again, not bothering with the rest of the record. In the days that followed, I would put that song on and stand in the middle of my bedroom with the door closed, switching from air piano to air guitar and singing along about going “home with the armadillo,” imagining myself on that little stage in that little place called Luckenbach (“population: 3”) that I’d been through once for just a brief minute when I was younger, soaking in all that applause and wallowing in the pure, ecstatic abandonment of the crowd. You could hear it all so clearly: The people fortunate enough to be there at that moment in time were absolutely losing their everlovin’ minds. Has there ever been a more joyous-sounding audience?

The only question I had was: “Who is this Gary P. Nunn?” At the end of the track when everybody’s whooping it up and I suppose throwing their cowboy hats in the air, some dude steps up to the mic and proclaims, “That was Gary P. Nunn!” while some other dude, presumably Mr. Nunn himself, is audibly glowing: “You make me feel so good.”

It didn’t make any sense. This song, “London Homesick Blues,” is the epic final track on Jerry Jeff Walker’s own album, and it’s a barn-burnin’ showstopper. It’s as good as a record can get.

And, again, Walker’s name is on the cover.

So — who is this Gary P. Nunn?

In the liner notes, Nunn gets thanked for “his musical head,” and, in a kind-of follow-up to that understated nod twenty-four years later, in 1997, Walker wrote this about him:

“Gary P. Nunn’s talent was at the core of the Lost Gonzo Band I used on my first three or four albums in Texas. Without Gary’s artistic vision and musical leadership, I would not have enjoyed the same amount of success that I have. Thanks, buddy.”

Now, what I’m about to write next I have trouble believing myself, but it’s the truth: Fifty years to the day after Gary P. recorded that anthem in the old dance hall in Luckenbach with Jerry Jeff and crew, and something like thirty years since I first laid ears on it, I found myself sitting across from him and his cowboy hat in a cafe booth a little ways outside of Austin, eating a lunch of biscuits and scrambled eggs and talking about his time with that Lost Gonzo band.

It began in January 1972 when Michael Murphey asked him to pick up a bass to fill the slot Bob Livingston was vacating as he split for Three Faces West (a group which featured fellow future star in the ¡VT! constellation Ray Wylie Hubbard). A very short time later, after completing his debut album for A&M Records with Nunn’s assistance, Murphey assembled the first iteration of the group that would become The Lost Gonzo Band, moving Nunn over to piano when Livingston returned to the fold.

—

So, Robert Plant said y’all were the best band he’d ever heard.

GP: Yep.

And that was when you were [backing] Michael Murphey in California, right?

GP: Yeah, we went out there for the record release party of his first record, Geronimo’s Cadillac. And we did our debut, our release party, at the … it was either Troubadour or Whisky a Go Go, one of those famous rooms. I think it was the Whisky a Go Go.

And Robert Plant and Jimmy Page, they were just sitting out there?

GP: Mm hmm. After the first show, I remember walking off the stage, and I walk around and there was not much room between the stage and this walk, and there were two chairs that Robert Plant and Jimmy Page were sitting in. I remember walking by them, and Robert Plant says: [in exaggerated English accent] “Best fucking band I ever heard! Best fucking band I ever heard!”

[laughter]

Amazing. Which of the Gonzos would have been in that configuration? I guess it was you and Bob [Livingston] and, uh….

GP: [Michael] McGeary. Craig Hillis.

Oh, so the same group that was on ¡Viva Terlingua!?

GP: … And Herb Steiner lived in California, and Michael called him, asked him to sit in with us.

Is that where y’all met Herb?

GP: It’s where I met him. Michael [Murphey] knew him from out there, ‘cuz he’d been out there before he came [back] to Texas. And they were all kind of part of that L.A. country scene, you know, like Linda Ronstadt and the Eagles.

… So this is around about the time that Jerry Jeff Walker blew into Austin from Key West, and Murphey lent him his band to make a record for MCA; the result was self-titled but is referred to by the Gonzos as “the brown album.” Shortly after that, the band was back in the studio with Murphey recording his next one, Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir.

Gary P.’s multiple talents and adaptability were an asset to both camps. In his book, At Home With the Armadillo, he writes of a telling event when he was in the sixth-grade band at school:

“I … played the trumpet, but my band director wanted me to give it up and convert to a baritone horn. … I was disappointed, as my goal was to be the first-chair trumpet player and the star of the band, and the baritone horn was definitely not going to make anyone a star. … Being flexible and versatile would be a recurring theme in my life. It seems I was always the utility man, assigned to filling the slots that were necessary, but not glamorous; doing the things that nobody else wanted to do, like playing secondary or supportive roles. … In the long run, it served me well and laid a solid foundation for my career.”

Drummer Michael McGeary told me this about Gary P.:

“[Concerning the band’s back-and-forth] shifting from the Murph headset to the Walker mindblow … Gary is the oil in that machine.”

By this time the group was firing on all cylinders, and Walker had a minor radio hit with “L.A. Freeway” from the brown album.

GP: I think we cut “L.A. Freeway” in the studio in New York. … Well, maybe parts of it; I remember doing the piano riffs at the beginning at that funky studio with no mixing board on 6th Street in Austin. We might have been on tour with Michael Murphey in New York, and Jerry Jeff just coordinated, ‘cuz they’d do that a lot.

That’s the impression I get. I think he was [in New York] mixing the brown album, and you were there [playing] at The Bitter End with Michael Murphey.

GP: Could be, yeah. ‘Cuz we were playing with Murphey, and Jerry Jeff would hire us on the same bill. You know, we’d put a double book on ‘em. We’d just switch back and forth, so I can’t remember precisely who we were on tour with, but … that would’ve been ‘72 so we would’ve been out with Murphey then.

And that would’ve been right before you left Murphey, pretty much, right?

GP: Let’s see … [the rest of the band] split with Murphey after [1973’s Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir] record.

And it was over pay or something, wasn’t it?

GP: Yeah, it was over pay. They went straight to Jerry Jeff because he had just … they had just released the brown album, and “L.A. Freeway” was the single. So they were booking Jerry Jeff on the West Coast. I stayed with [Murphey] ‘cuz I had a cut on [Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir].

I love that one. “South Canadian River Song”?

GP: “South Canadian.”

I hear The Beatles in there. I hear Harry Nilsson in that, too. It’s not so much country as baroque pop almost, you know? The way that song builds, and the lyrics are great, too, like “the water over my head” and all that.

GP: Yeah. “Over my head is beyond what I know.”

Did you write any others on [Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir], or is that the only one?

GP: That’s the only one. That was the first one. Murphey just built that song on a piano piece that I did. I used to just make up these piano pieces. You know the Gonzos song, uh, it’s an instrumental called “Comanche Highway”? It was on that Rendezvous record that we did later on. That was typical; I would just make up these things on the piano, and they’d eventually end up being a song. Or just an instrumental.

“South Canadian River Song” is one of my favorites.

GP: It is a good song. But it was about half finished at that point. And that was the first opportunity I had to get a song on a record, you know. Get a songwriting credit. So, I was more connected [to] and believed in Michael. I really thought he was great, you know. So I stuck with him – just out of loyalty for one thing. Second of all, because I really thought he was a great artist and still do. So they went with [Walker], and I stayed with Michael. I think it was in the spring when all that went down. Probably in early ‘73. Michael and I went around doing singer/songwriter things. You know, in those days they had what they called the college coffee-house circuit. You had these booking agents; they’d book these singer/songwriter acts in the colleges, and so we did several of those that summer or that spring. Actually, we went to London. You know, that’s when – about the first of March – was when Michael went to London, and he asked me to go with him. So we spent a month over there. And that’s when I wrote “London Homesick Blues,” while we were there.

You have said that you considered it almost a writing exercise. You weren’t even really thinking of it as a….

GP: No.

Which is amazing because it’s obviously such an anthem now.

GP: I was just killing time, you know, playing with … trying to mix British phrases with Texas phrases, back and forth, you know. And it got to be fun there after a while. “Put up your dukes” and “London Bridge is falling down.” So, it was just a kind of a fun exercise to kill time. I was there in this flat for days on end. [While Murphey was out and about in London doing PR and meeting the likes of Paul McCartney, Nunn was bored and freezing his ass off in Murphey’s brother-in-law’s bachelor pad.]

So, I’ve read that the version of “London Homesick Blues” on the album is the second take.

GP: Right.

And I’ve also heard that that tag at the end is actually from the first take, and that it was edited together. Is that right?

GP: Right, yeah.

Because somebody broke a string or something?

GP: Well, um, when we finished up the first take, [producer] Michael Brovsky rushed in, and he said, “You’ve got to do it again; we weren’t ready for you.”

Like maybe it wasn’t fully taped or….

GP: Yeah, for whatever reason, but that’s what he said. He said, “We weren’t ready for you.” You know, a mix, or whatever. He said, “You gotta do it again! You gotta do it again!” You know, I was on cloud nine at that point.

You had to be. It sounds like euphoria on the record.

GP: I’d never been in a situation like … so much approval and applause was cast in my personal direction. [His remark at the beginning of the track, “Gotta put myself back in that place again,” does double duty in reference to both London and the yet-to-be-exalted state of mind he’d been in just minutes earlier.]

On the record, it sounds like the place is exploding.

GP: Yeah, it did. Yeah.

Was it better that y’all went with the second take? Did you get to work out any of the kinks that maybe you didn’t have worked out the first time through?

GP: Well, to me, I was in such a state of, you know, just … there’s one point on it [where] I’m playing the piano, I’m like dah dah dah…. I don’t know if it’s the second or third verse; if you go back and listen to it, it’s like, when it changes the chord, I don’t change the chord. I sit there and hit the wrong chord all the way through it.

Really? I’ve never heard that!

GP: So nobody noticed it. It was like Jerry Jeff used to say: “When you’re fucking up, don’t flinch.”

[laughter]

And that’s kind of like the Miles Davis thing, right? Like, if you make a mistake and repeat it two more times, it’s not a mistake anymore?

GP: That’s right. So, I mean, I realized what was going on … ‘course I was trying to remember the words, too, and the excitement and everything going on, I was, uh….

I don’t know how you kept it together, in all honesty. ‘Cuz y’all hadn’t even planned on playing it, right?

GP: No.

It was kind of like calling an audible. [Walker] was like, “Hey, let’s play that song.”

GP: Yeah, and it had never been rehearsed. It was just a total wing-it situation. [Truth is, this is one of those legends that has been repeated so many times over the years that, until recently, nobody has questioned it. On February 2, 2025, Gary P. (and the rest of the original Gonzos) took part in a panel discussion at The Wittliff Collections at Texas State University in San Marcos, Texas, where newly uncovered tapes of rehearsals and outtakes were played and revealed that the band had gone over “London Homesick Blues” at least a couple of times before playing it in the Saturday show. Gary P.: “All these years I have had no recollection of that, and I have spread the myth that the song had never been rehearsed or played before. I need to correct that.”]

Have you always gone by Gary “P.” Nunn, or did that start when Bob announced you that way at the end of the song? I noticed you’re simply listed as Gary Nunn on earlier albums.

GP: When I was in high school, I started signing my name Gary P. Nunn. Still, everyone called me Gary Nunn. Thinking about it, you could say that I was officially and publicly tagged “Gary P. Nunn” when Bob called out my name during the live recording of ¡Viva Terlingua! in 1973 at Luckenbach, as I have been using it publicly ever since.

I want to know what the environment was like that week. According to Dale [Ashby] and Len [Ognibene] [of Dale Ashby and Father, location recording], it was very friendly; it felt like a family thing. There weren’t any fights or anything.

GP: No.

I mean, I always heard that Jerry Jeff could get into it and get his nose busted, but….

GP: Maybe by one of the guys in the band….

[laughter]

GP: Well, we’d go over [to Luckenbach] about … we stayed in Fredericksburg [Texas] at the Peach Tree Inn. You know where Highway 87 hits 290? Just across Barons Creek. The Peach Tree Inn. It’s still there and it still looks pretty much like it did back then. It had various cabins, separated cabins. So we stayed there; we’d get up 10-ish or so. Out there on the highway was this little strip mall thing; I think it’s an antique store now. We’d go eat breakfast in this place, and probably by about 11 or 11:30, we’d arrive in Luckenbach. It was just very, very quiet at that time of day, early in the week. They’d open up the dance hall and the beer joint, and we’d generally just kind of mosey into the hall and pick up our instruments, and we didn’t know exactly what Jerry Jeff was gonna do. Sometimes we might just jam or do soundchecks. Early on, as I recall, the first track that we did was, uh, just guessing, but “Gettin’ By,” the first track on the record.

And that was kind of written on the spot, wasn’t it? ‘Cuz I remember reading that y’all went down there without very much written. Which seems to be held up by what’s on the album, right? At the last second they asked for your song, and at the last second y’all did Ray Wylie Hubbard’s song. And [Jerry Jeff] covered Michael Murphey and Guy Clark. So, “Gettin’ By”….

GP: Probably some of the lyrics … he probably had a brief outline of how it went, you know, and first verse and the chorus or something like that. Winging it, ‘cuz he’d, you know … “Pickin’ up the pieces; just gettin’ by on gettin’ by.” Makin’ it up as we go.

Do you remember what day of the week you would’ve gotten there? ‘Cuz Saturday was the concert, right?

GP: I think we went out there on a Monday.

And Dale would’ve already been there hanging the mics in the trees and everything?

GP: Mm hmm. Well, uh, maybe the hanging the mics in the trees is just an idea that evolved, because after … normally after a day’s sessions and way into the evening, when we’d retire over to the beer joint under the trees where the chickens were going to roost and everything and Hondo [Crouch] would be there, and, you know, he’d quote [his poems] “Luckenbach Moon” or “Luckenbach Daylight” or just keep us entertained. For a while we might just pick a few songs for fun around the trees at the end of the day. Well into the evening, probably, up towards midnight normally.

There’s those songs where you can hear the crickets.

GP: Yeah.

And so I always wondered if that meant it was evening, or if maybe they just chirped all day long.

GP: It was very late at night, and there was nobody else around. It was just us, and the windows [of the dance hall] were open.

One of the songs that you can hear the crickets on is, um …

GP: “Wheel.”

… “Wheel.” But, according to Bob Livingston’s anecdote, [it sounds like] that was done maybe Sunday morning when you all thought you were going home, and you showed up….

GP: No, it was late in the evening.

According to [Livingston], everybody thought everything was done ‘cuz the show was over, and you all showed up at Luckenbach, and [Jerry Jeff] said, “I’ve got one more song.” And that you did “Wheel.” But it sounds like nighttime, so I was kinda trying to piece that together.

GP: It definitely was nighttime. I definitely have a different recollection of it. It was late in the evening, and it was, you know, something Jerry Jeff wanted to get done, and the mood was right.

Well, according to the story, everybody was high out of their minds, and could barely play and somehow pulled it off.

GP: Nah.

You don’t remember it like that?

GP: We weren’t high out of our minds. We had a little buzz going. Kelly Dunn had passed around little hits of window panes, you know? Just tiny little hits, you know? We did that after breakfast, or something like that, that day. And, by the end of evening, you know, it was just a little sparkling tingle of it going on. You know, it wasn’t like everybody was buzzed and tripping and all that.

I think Bob’s exact story is that he felt like he was floating above Luckenbach and that Jerry Jeff reached up and dragged him back down to do “Wheel.” Bob’s a good storyteller, I gotta say.

GP: Yeah, he is.

—

Waitress: You guys still working on that?

Me: I’m actually finished.

GP: Oh, let me nibble a little bit more here.

Waitress: OK, just making sure you guys are good.

—

So, ¡Viva Terlingua! covers so much ground musically. “Gettin’ By” is a two-beat thing, kind of like “Jambalaya,” like a Hank Williams thing.

GP: Oom-pah, oom-pah, oom-pah.

And then you’ve got that Guy Clark ballad. And then “Sangria Wine” is kind of a weird attempt at reggae, right?

GP: Well, that was Michael McGeary’s influence. You know, I write in the book about Public Domain [a little cluster of living spaces around a kind of courtyard that was off North Lamar in Austin], where we lived in all those cabins where a series of musicians … Michael was living in that cabin, and early on I’d never even heard of reggae music. I went out the back door, and he had his door open and the stereo turned up, and, you know, like, “The Harder They Come” or, what’s that … “I Can See Clearly Now,” and that kind of stuff. You know, “I Shot the Sheriff.”

So that was the first time you’d heard it? Was coming from Michael McGeary?

GP: Yeah. [McGeary] was from San Diego, California. He was kind of a hip dude, a California dude. And he had a California sort of attitude about him, too; that was fun. So anyway we started just playing with the idea of reggae, not knowing any of the basics or anything.

Right. You just kind of knew it was an off-beat….

GP: Yeah, and [guitarist] Craig Hillis came up with that diddle-iddle-id, diddle-iddle-id. And you know Bob, he was on the bass, bum-bum-bah; you know it’s just funk at its most elementary, an attempt at doing reggae. But it’s a blend of us and reggae. It worked out. Of course, everybody loved that song.

It’s great, and I also have the 45 of it, and I always wondered why y’all re-recorded it. ‘Cuz the 45 was a different version.

GP: Is that right?

Yeah, it’s not the ¡Viva Terlingua! version. It’s more of a studio version. It loses some of that feel. You know, the looseness.

GP: Yeah, you never can do it over again.

“Little Bird” is [Walker] pulling one of his old songs out. And then “Get It Out” is a weird one.

GP: I’ll tell you a story about that. Jerry Jeff brought it to us, and it had a part in it that there were only three measures to a bar. And me, I’m an old bass player. I started out on drums and moved to bass, and so basically I’m a bass player, and I look at things in terms of regular 1-2-3-4, so I noted that there was a measure that doesn’t have four beats. So I set up a four-beat thing in my head. And I came up with the duh duh duh … bum. You know, that’s kind of how it starts. Me and the fiddle. I’m on the Wurlitzer piano and “Sweet” Mary Egan on the fiddle. I had showed it to the band, and we’d get there an hour, an hour-and-a-half before Jerry Jeff’d ever arrive. So we’re killing time; we got in there one day and I had this in my mind, and I just kinda laid it out for ‘em. You know, around this figure, duh duh duh … bum. It came out four beats to the measure. When Jerry Jeff got there and he heard us doing it, he was: “Let’s cut it.” And so I pretty much arranged it. That was the exception rather than the rule. [Usually,] when Jerry Jeff arrived, and after a few minutes of tuning and reviewing his notes, he would decide which song he wanted to do.

One other thing I personally hear in it, in the second half of the song, [Hillis] starts doing kind of a chugging guitar line, and what it sounds like to me is an old Sam and Dave song, “I Take What I Want.” It almost has a Stax Records feel to it. There’s a guitar line in that, and it sounds to me like what Craig’s doing. And so, to me, “Get It Out” has this kind of R&B feel.

GP: And it breaks down into half time, you know, for the chorus.

Michael Murphey’s “Backsliders Wine”: What’s interesting about that one is that you [and Bob] had already played it with Murphey [on his 1972 album Geronimo’s Cadillac]. … You basically covered yourselves.… just with a different singer.

GP: Yeah.

But it got slower.

GP: And Jerry Jeff put a little twist on it. He always would make it his own, sort of.

It definitely gets a bit more like a drunkard’s lament when Jerry’s doing it than when [Murphey] was doing it.

GP: Yeah, Murphey’s was like a First Baptist comment on his relationship with his mother … and the First Baptist view of drinking, you know. Heh. Yeah. Jerry Jeff, he nailed that one.

Yeah. The whole album is just … it sounds magical, you know?

GP: Well, I was just gonna say, it’s kind of like a Hill Country fairyland. You know? And Hondo [who was Jerry Jeff’s good friend and one of the three owners of Luckenbach] was the Grand Imagineer, the Pied Piper, just this charming, enchanting figure that … you know, he was always doing that thing. He’d come down and just be the Hill Country rancher cowboy guy. He always was entertaining you; he was out in front of you; he would set you up for a joke, to tell you a story, to make a point of something. He was always out there in front of you, kind of, like, edgy, before he’d pull the string and the punchline of the story or whatever he set you up for. So, there was this feeling of magic. It was not a part of the rest of the world.

You know on [Jerry Jeff’s 1977 album] A Man Must Carry On there’s that recording of Hondo doing “Luckenbach Moon”?

GP: Mm hmm.

I assume that was actually recorded at the ¡Viva Terlingua! sessions. I’ve read that he was recorded doing it and that they couldn’t fit it on the record. So I was wondering if it was a holdover, the track that ended up on A Man Must Carry On.

GP: I’ll tell you an interesting story about that. I was always trying to make copies of things … that’s when I could get my hands on them, you know. Just board mixes, just a hobby of mine. A collection of songs. When it came around to A Man Must Carry On, Jerry Jeff called me frantically. He said, “Do you have a copy of Hondo doing ‘Luckenbach Moon’? We can’t find one anywhere.” It turns out I had the only copy.

And would it have been from the tapes that Dale Ashby had recorded? Or did you do it yourself?

GP: It was probably the mic in the tree, you know, [the same one] that picked up “Pick a little, talk a little, pick a little, talk a little, cheep cheep cheep….”

Oh, I love “Stereo Chickens.”

GP: That was another one of my things.

And you weren’t thinking of that as anything for the record. Y’all were just messing around.

GP: Yeah, we were just playing, because, see, as usual, after a day’s and evening’s recording in the dance hall, we would generally mosey over behind the beer joint and sit around under those old oak trees, maybe trade a few tunes, but it was usually Hondo holding court, telling humorous stories and reciting his Luckenbach poems; those were magic and enchanting experiences. Regarding the chickens, they were permanent residents of Luckenbach. One evening we had retired from the dance hall pretty early, as it was just about twilight time when the chickens would go to roost in the oak trees there. They were cackling and clucking away as they do while settling to roost and competing for the best positions, according to their “pecking order”! It reminded me of a scene from The Music Man in which women’s gossipy chatter was metaphorically likened in a song to the cackling of chickens. We played with it in high school choir. “Goodnight, Ladies,” this pick-a-little, talk-a-little thing. And so we were sitting out there, and I started doing that – and probably I’d done it with Bob at one point, too. So, I started doing it, and everybody picked up on it, and we got it on tape. They had the mics hanging in the oaks trees above and caught it live, and that was the opening, if I’m not mistaken, of the A Man Must Carry On album. [The liner notes for that album state that the track was “recorded from a tree / Luckenbach, Texas.”]

It’s so great, and, really, the idea of having those microphones on all the time was genius. It catches the atmosphere so well.

GP: Right.

Surely there was a recording of the whole concert, right? And it just got edited.

GP: Yeah. I never had, you know, access or was privy to that, the mixing process or….

Well, when [author] Jan Reid wrote The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock, he said that he had gone out to Luckenbach, I don’t know, within a year of ¡Viva Terlingua!, and he said somebody there was playing a tape of the whole concert. And I’ve always wondered if that tape exists and who has it; where it is? [See note about the Wittliff Collections above.]

GP: Hmm.

And maybe Jan didn’t know what he was hearing. Maybe it was something different. But he said it was a tape of the show. It piqued my interest, ‘cuz I was curious to hear the rest of the show, you know! There’s gotta be just hours and hours and hours of tape if those mics were running all the time. There’s gotta be so much stuff that was on the cutting-room floor.

GP: We did several [songs that] he used to do. What’s that song? … “Goodnight, Irene.” And then we played all the tunes that we’d recorded. We probably didn’t do “Wheel” or things like that, but we played most of the songs that we recorded during the week session and then finished up with, you know, “London Homesick Blues.”

—

Waitress: Are you like a country star or somethin’?

GP: Sorry?

Waitress: Are you a, uh, a country music star?

GP: Uh, I’m a songwriter.

Waitress: Oh, you’re a songwriter. Awesome.

Me: I consider him a star.

Waitress: Do you? I could just….

Me [to GP]: But I don’t want to embarrass you.

Waitress: I got little tidbits of, you know….

GP: I’m Gary P. Nunn.

Waitress: Gary P….

Me and GP [together]: Gary P. Nunn.

Me: He wrote that song, “I Want to Go Home with the Armadillo.”

Waitress: Oh really? Heh, that’s awesome. It’s nice to meet you.

GP: Nice to meet you.

—

Gary P. Nunn is an unassuming and generous guy … and completely underappreciated according to almost everyone I’ve talked to for this ¡Viva Terlingua! project. And this even though he’s been designated an official ambassador for Texas by two Texas governors, won several awards and honors, and written or co-written hits for the likes of Willie Nelson and Rosanne Cash. He managed to launch a solid career based on hard work and artistic integrity out of those wild-ass days in 1970s Austin.

The Gonzos had begun doing their own thing on the road and in the studio while they were still with Jerry Jeff, and they continued for a while after parting ways with him in the late 70s. Ed Ward, in his 1975 Rolling Stone review of their debut album for MCA, said they’d produced “one of the best albums ever to come out of Austin,” and he singled out Nunn as a “versatile and engaging songwriter.” Village Voice critic Robert Christgau said the album would “probably stand as the best by a new group this year” and praised Gary P.’s “understated rock and roll eloquence.”

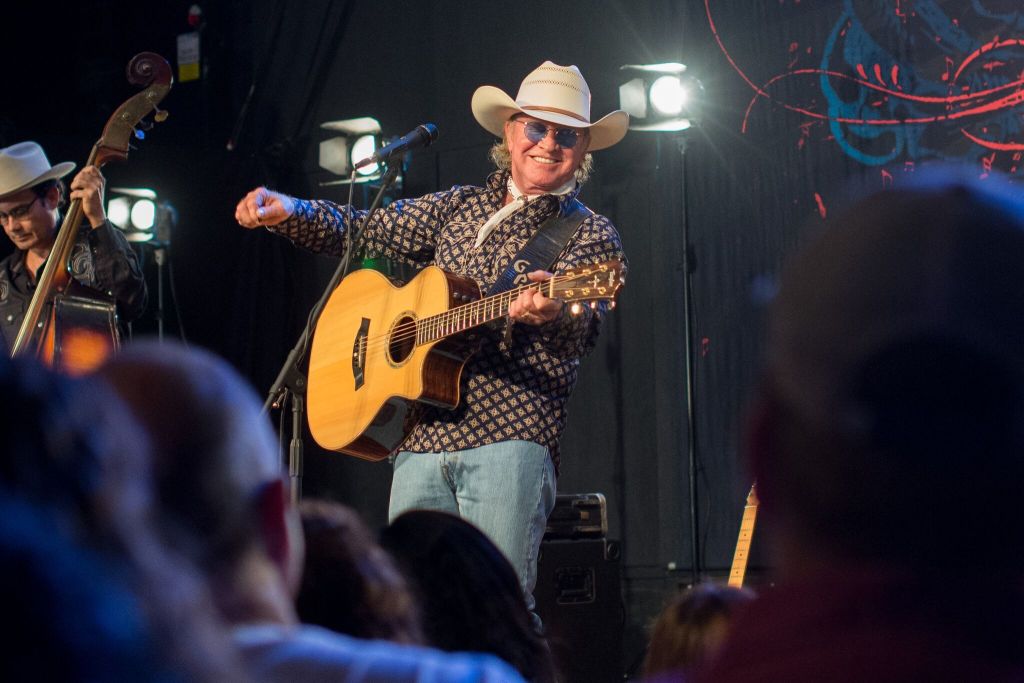

When that period came to an end, Gary P. embarked on his own decades-long odyssey of leading bands, making solo albums, touring from Texas to Europe and back, starting his own record label, and discovering and promoting new artists and songs every step of the way. In his autobiography, he called himself a “microcosm of the music industry.” He also started taking photographs in 1976, documenting the people and places he encountered along the way. Several of his pictures are currently on display at The Wittliff Collections in San Marcos, Texas, and he plans to work on publishing a book of his images, “if and when” he retires from performing.

But he’s still at it. His latest album, To Texas, With Love, two-steps all across the state and kicks off with a song that proclaims: “I’ve been around the world, and I’ve never found a place that makes me feel this good / No, I wasn’t born in Texas, y’all, but I got here as quick as I could.”

Did I mention he was born in Oklahoma?

-30-

Leave a comment